3.1. Usability

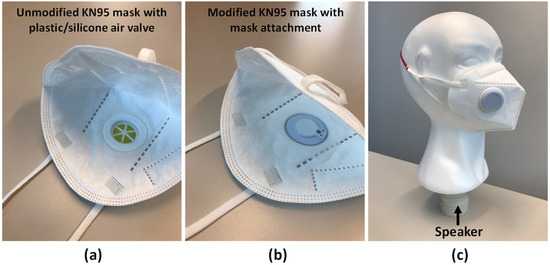

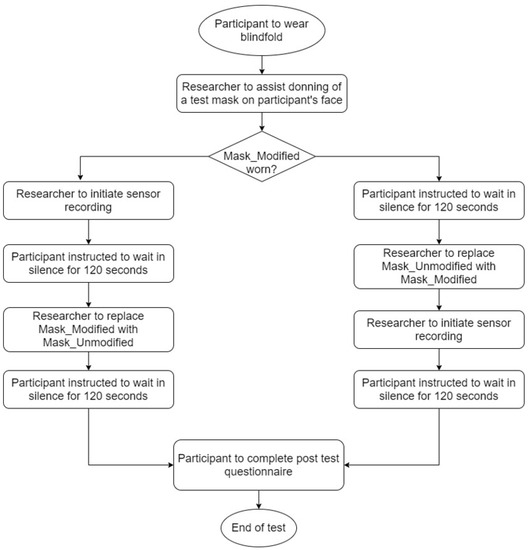

The success of a human-centered product design for any functional mask attachment can loosely be represented by the inability of the wearer to differentiate between wearing a mask with and without the attachment or experiencing any hindrance in human performance. As a qualitative analysis, 16 participants were asked to describe their experience according to the study design described in the earlier section, which involved deprived visual-sensory interaction of the participants with two masks. One of the two was modified with the mask attachment.

Ten out of 16 participants felt that the two masks were different. One participant expressed that the “motion of the sensor” was felt for the modified mask, and another reported that the sensor could be felt on the unmodified mask. As the mask attachment is a non-moving part and the unmodified mask does not contain the mask attachment, these two participants’ experiences were inconsistent with the facts. Three participants reported the unmodified mask was more breathable, while two others reported the opposite. One of the two who reported the opposite said it may be due to the “tightness of the mask” worn on the unmodified mask. However, the tightness was not mentioned before the data collection session.

Five participants correctly reported the modified mask was slightly heavier than the unmodified mask. Nevertheless, no participant reported any significant discomfort experienced during or after the study.

3.2. Respiratory Rate Estimation

The normal range of resting RR for adults is 12–20 breath per minute (brpm) [

24]. shows that the resting RRs of 12 recruited participants were within the normal range, while the resting RRs of three others were above normal.

Table 2. Comparison of resting respiratory rate between the mask attachment and manual counting for spontaneous breathing.

The algorithm could accurately measure RR in all ranges, including the range that is outside of normal range (i.e., >20 brpm). The RR estimation algorithm’s smallest and largest mean absolute errors were 0.2 brpm and 4.0 brpm, respectively. Autocorrelation function has also been proven useful in extracting the periodicity of quasi-periodic physiological signals [

25]. However, the accuracy of such a method decreases with increasing inter-period variability of RR. The results showed that the RR algorithm achieved an overall high accuracy (with a mean absolute error of 2.0 ± 1.3 brpm) among the 15 participants. The reference of participant 3 was not available as the breath sound recording was not heard by the annotators. Thus, the results of participant 3 were excluded from the study.

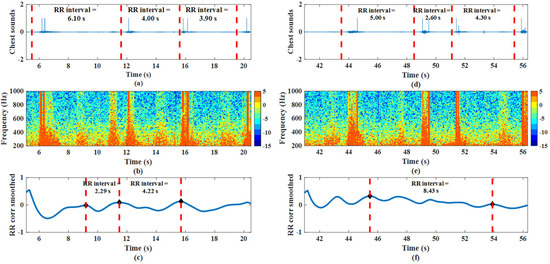

The main challenge of the RR estimation algorithm was to accurately identify the inspiration and expiration of a breath and calculate the number of repeated patterns within a 15-s window, especially in cases where the duration of inspiration and expiration is equal.

demonstrates the risk of overestimating and underestimating the RR. a,c showed that the actual RR was 12.9 brpm, but the RR algorithm was estimated as 18.4 brpm. b shows a burst split in the exhale between 10.5 s and 12.5 s within the same breath cycle. This may have contributed to the overestimation of the RR algorithm as it considered this short period of breath cycle in the evaluation window. Conversely, d,f demonstrate the risk of underestimating the RR. The actual RR was 15.1 brpm, but the RR algorithm estimated 7.1 brpm. Such error occurred because the breath patterns were irregular (higher variability in the duration of inspiration and expiration and period of breath cycles within the evaluation window), and that was challenging for the algorithm to detect the global peaks in the autocorrelation plot in f.

Figure 3. A short segment plot of (a–c) participant 10’s recording (estimated RR > actual RR) and (d–f) participant 10’s recording (estimated RR < actual RR) in the time-domain between 200 Hz and 1000 Hz, time-domain entropy plot of breath sounds, and autocorrelation plot of entropy signals.

Even though the gold standard of respiratory rate monitoring is capnometry, the most common method while the most common method used in the clinic is manual counting by healthcare professionals [

26,

27]. Nevertheless, manual counting of RR is labor-intensive and unsuitable for continuous or prolonged RR measurement, especially for healthcare facilities that had been overwhelmed.

Still, manual counting of a one-minute sample recording is widely practiced in various evaluation protocols [

28,

29,

30]. For this reason, only a one-minute sample was recorded for each subject for the evaluation of the RR algorithm. As the RR algorithm computes a 15-s segment data, with an update rate of 5-s, there will be 10 RR outputs in every one-minute recording. This is sufficient to validate the RR algorithm to prove a new application concept.

3.3. Wheeze Detection

The WZ detection algorithm was originally designed to work on chest sounds, using two low-complexity time-based spectral entropy features to differentiate wheezes from normal breaths. In the present study, another feature, frequency-based entropy difference, was added to the WZ detection algorithm to improve classification accuracy. As listed in , the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of the simulated tracheal normal breaths and wheeze classified using a support vector machine (SVM) model with a radial basis kernel function were 88.8%, 94.9%, and 91.9%, respectively. Thus, the wheeze detection algorithm shows a balanced trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, which is an important criterion for a “good classifier”. In addition, the model performance was evaluated using a 10-fold cross-validation method to show that the model was robust when tested in 10 different scenarios.

Table 3. Performance of wheeze detection algorithm.

Even though a mannequin with a speaker does not represent an actual wheezy patient, it is a reasonable simulation that shows the direction of sound from the chest level through the airway to the sensor attached to the mask for a proof-of-concept study as simulations have been used in other studies [

31,

32]. In future studies, the wheeze detection algorithm will be validated in a clinical trial with actual wheezing patients.

The current study shows that the acoustic sensor is versatile for a different application, i.e., a mask attachment. Functionally, the original intended use of the sensor at the chest level provides a more comprehensive cardiopulmonary monitoring as it also estimates heart rate together with RR. However, the current proposed application provides an easier mode of administration and a more comfortable solution (with no direct surface contact of the sensor with the patient) to remotely monitor RR and detect wheeze. Notably, RR has also been recognized as the first indication and the best marker of deterioration in a patient’s conditions [

33]. Therefore, the results from the study support that the proposed mask attachment can help manage patient conditions in overwhelmed clinics.

Yuriy Ilkovych -

December 17, 2025 -

Pulmonology -

43 views -

0 Comments -

0 Likes -

0 Reviews

Yuriy Ilkovych -

December 17, 2025 -

Pulmonology -

43 views -

0 Comments -

0 Likes -

0 Reviews